When considering the qualities needed to lead an organization, especially in times of disruption and uncertainty, the ability to adapt is often one of the most coveted qualities for leaders. As such, I’ve reflected on the tremendous amount of change and adversity that we have collectively faced as a result of the challenging but necessary COVID-19 lockdowns. In the past months, just as businesses were on the cusp of returning to the office and resuming normal routines, the Delta variant quickly demanded laborers and managers to alter their course and reconsider how to keep employees safe.

This is only one of the more recent examples of the disruption we have experienced in the past two tumultuous years. Factors like variants and spikes in infections make it apparent that this need for an adaptable and responsive approach to leadership will continue to be the norm. But one thing that will impede progress and growth is panic. With this in mind, I believe that leaders and managers must take a step back to look at the full-wide picture before proceeding with new strategies moving forward.

But simply being able to “adapt” or showing “adaptive actions” is not enough: organizations that wish to employ an adaptive leadership style must cultivate a few key characteristics to ensure optimal performance. In recent years, many business leaders have realized that the single-figure, top-down leadership model is outdated and impractical. No single person can solve every problem, which brings in the need for adaptive and collaborative leadership.

While leadership styles have been transformed over time throughout the years, adaptive leadership, in particular, embraces learning and continuous growth. Leaders shouldn’t be afraid to try new tactics to solve problems. They should also encourage innovation and creativity from their employees, even if the solutions don’t always work.

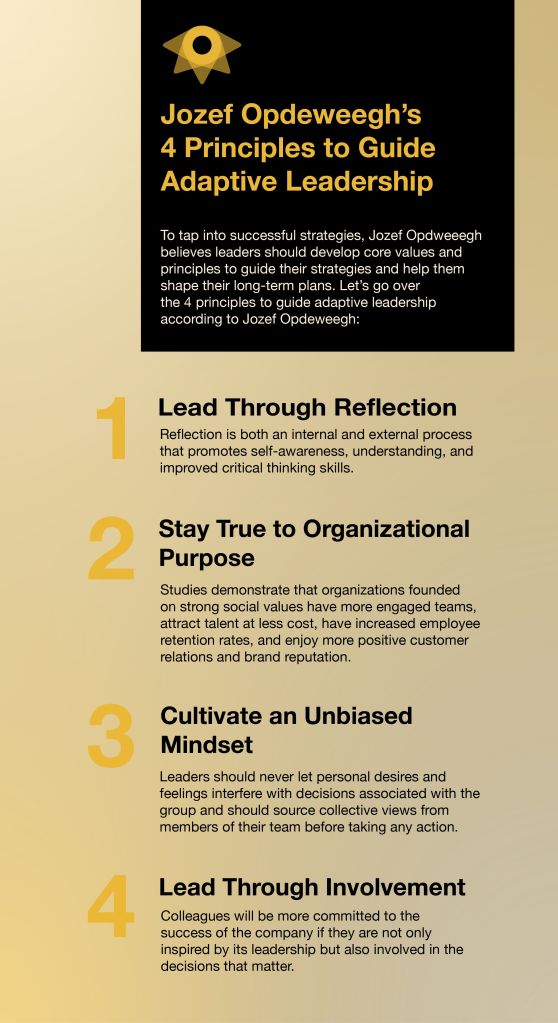

Let’s go over the 4 principles to guide adaptive leadership:

- Leading Through Reflection

Reflection is both an internal and external process that promotes self-awareness, understanding, and improved critical thinking skills. Learning to be present, aware, and attentive to our experience and interactions with people throughout the day is an important element of adaptive leadership.

- Developing Clear Organizational Purpose

Studies and surveys demonstrate that organizations founded on strong social values have more engaged teams, attract talent at less cost, have increased employee retention rates, and enjoy more positive customer relations and brand reputation. Leadership in the next decade will require greater attention to these issues, not only as a requisite of political correctness but as a means to drive performance.

- Cultivating an Unbiased Mindset

An ideal group leader should take a selfless and unbiased approach to leadership and credit the company’s success to the contributions of every member and not himself alone. As such, leaders should never let personal desires and feelings interfere with decisions associated with the group and should source collective views from members of their team before taking any action.

- Leading With Empathy

Employees will be more committed to the success of the company if they feel inspired by leadership. A successful company generally boasts a roster of employees who enjoy working there. Giving employees a voice, equipping them with the knowledge they need to succeed, and inspiring them to drive the company forward is beneficial to the company at large.